Before we move into this lesson,

let’s look at the answers to the question from the first installment. Here, in

review, are the questions: I.

What is (a) the dominant

of the B Major scale, (b) the mediant

of the D Major scale, and (c) the submediant

of the F# harmonic minor scale? II.

What degree of the scale is (a) C in A¨ major, (b) C in A minor, (c) G¨ in D¨

Major, (d) G# in F# minor, and (e) C in F Major? III.

What note is (a) a minor third above C, (b) a major

sixth above B, (c) a perfect fourth above D¨,

(d) an augmented fifth above A¨,

(e) a diminished fifth above D, (f) an augmented fifth above A¨, (g) a major third above F#, (h) a major second below E¨, (i) a perfect

fifth below B, and (j) a minor sixth below C? IV.

What is the inversion of (a) a major third, (b) a

perfect fifth, (c) an augmented second, (d) a minor seventh, (e) a major sixth,

and (f) a diminished fifth?

And the answers: 1)

(a)

F#, (b) F#, (c) D 2)

(a)

mediant, (b) mediant, (c) subdominant, (d) supertonic, (e) dominant 3)

(a)

Eb, (b) G#, (c) Gb, (d) E,

(e) Ab, (f) E, (g) A#, (h) Db, (i) E, (j) E 4)

(a)

minor sixth, (b) perfect fourth, (c) diminished seventh, (d) major second, (e)

minor third, (f) augmented fourth

It may seem like Greek to you, but review the last installment and

you’ll see. But more importantly, if you just stick with it, as with anything,

you will begin to make sense of what is being discussed.

Now to continue…

An interval is the distance between two notes, and all chords are made

up of intervals. Two notes sounded together constitute harmony, but a chord is

usually considered to have at least three notes (though two notes can suggest a

chord, but no more than that). Pairs of notes (intervals) are the raw materials

from which chords are built, and the raw materials of intervals are single

notes.

Different intervals have different qualities of sound; how an interval

is played depends upon the desired effect. If you play C and then E, the effect

is melodic; if you play them together, the effect gains a harmonic dimension.

Intervals can be divided into groups by the kind

of aural effect they have. Being able to identify intervals by ear is a

considerable advantage, and knowing how to categorize them enables you to tell

the difference between one and another. The two main types of intervals are consonant

and dissonant.

Consonant intervals sound pleasing, or at least comfortable, and they

include the perfect intervals (perfect octave, perfect fourth and, perfect

fifth), along with the major and minor third and the major and minor sixth.

Dissonant intervals sound unpleasant, aggressive, uncomfortable (think

fingernails on a chalkboard), and include the major and minor second and the

major and minor seventh. The dissonant tritone (augmented fourth or diminished

fifth) sounds vague and a bit lost, and not so annoying.

Learn to recognize all the intervals by sound so that you know what

interval you’re listening to and what its character is. Remember that it’s

easier to learn the character of a sound first, and then to identify the

interval. Intervals can be further divided and described in this way: Perfect intervals: Strong,

empty-sounding, dignified – make up your own adjectives. They sound satisfying

in themselves and don’t sound as if they need to be resolved. Thirds and sixths: Pleasing,

harmonious, friendly, cozy. Seconds and sevenths: Unfriendly,

aggressive, nasty – you couldn’t imagine playing one and then just leaving it

at that with nothing to follow it. Augmented fourth or diminished fifth: Unsatisfactory in a

vague sort of way. Not aggressive, but not comfortable.

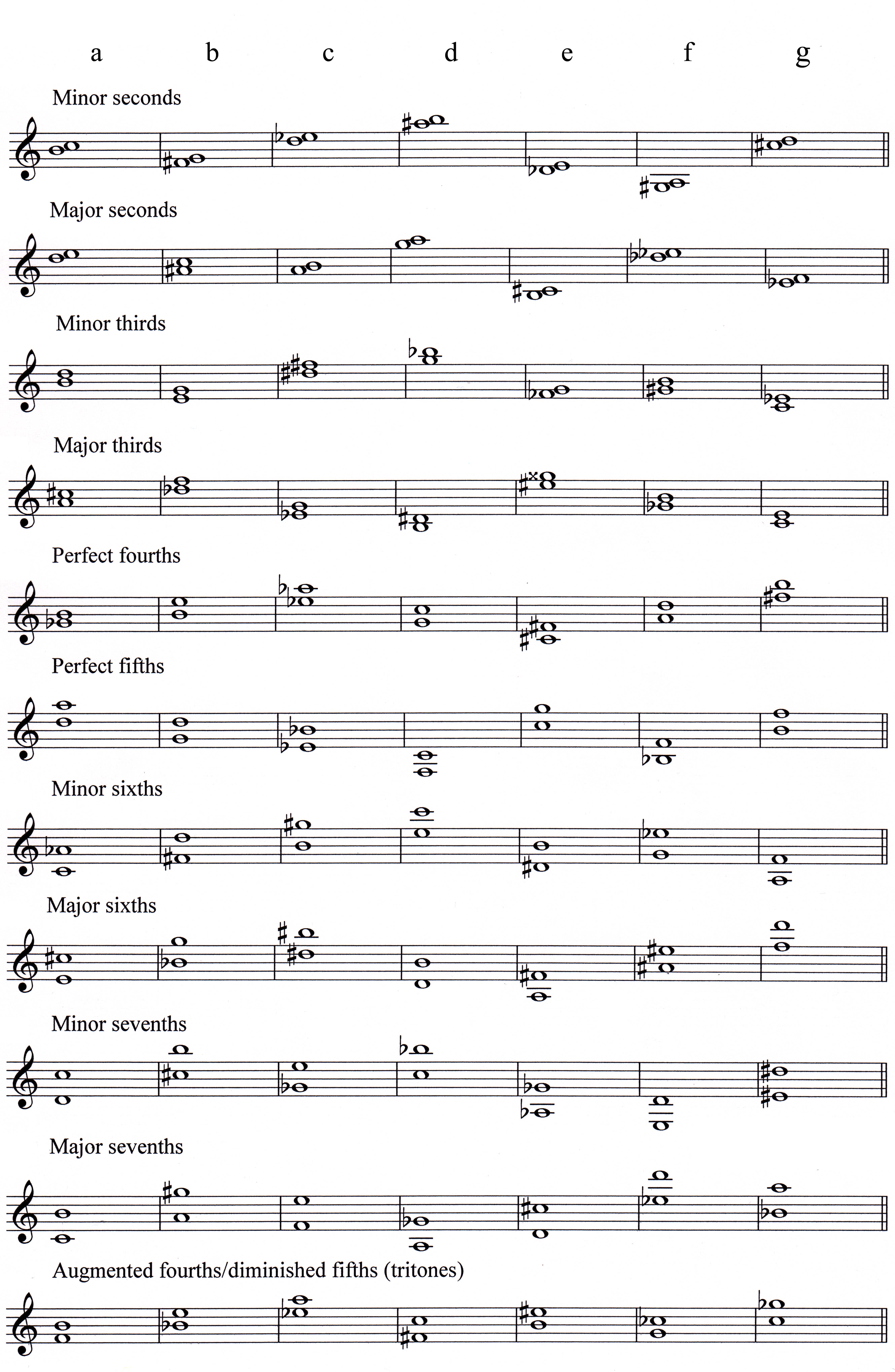

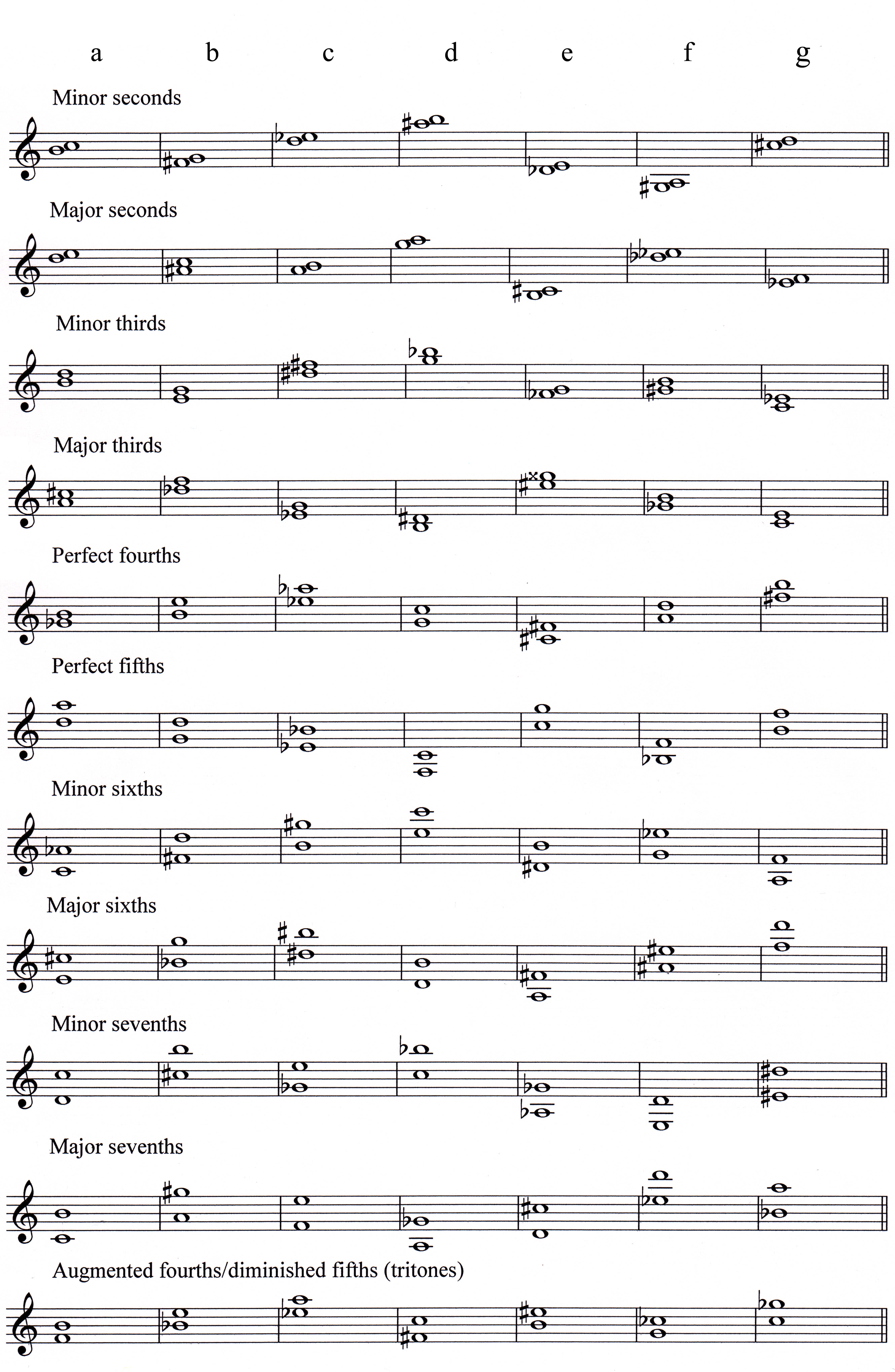

In Ex. 1, there are samples of each kind of interval. Play them and listen

to them carefully, concentrating first on the way they sound. (To keep you on your toes, each group contains one

interval that is either wrongly notated or is not one of the right sound; the

answers are at the end). Make up your own examples to add to these. When you

can successfully identify their types from their sounds (it’s helpful to have

someone play them for you, so that you don’t know what notes you’re listening

to), then try to identify their size.

More descriptions you might find helpful: Both thirds and sixths sound

friendly: The Thirds are close friends; sixths are just friends. Seconds and

sevenths both are aggressive; seconds fight hand-to-hand combat, while sevenths

shoot across the street at one another. The final step is to ascertain whether

a third or sixth is major or minor.

There are, of course, more interval names

than interval sounds – with only 12

semi-tones in an octave, there can only be 13 different interval sounds (for

instance, an augmented third such as E to C#

is the same aural size as a perfect fourth such as E to F). Since they can’t be

differentiated by ear, we confine ourselves to the simpler and more useful

interval names.

Did you spot the booby-trapped intervals in Ex. 1? The following

examples have the right sound, but they are notated incorrectly: major second

(b); minor third (e); perfect fourth (a); minor seventh (c).

These intervals are wrong altogether: minor second (e); major third (f);

perfect fifth (g); minor sixth (c); major sixth (f); major seventh (d); tritone

(f).