You've probably heard of the "Nashville" numbers system, maybe not. It's a system for players to quickly grasp how to play songs. It was created many years ago because many of the studio musicians, who were phenomenal

players, couldn't read music. Handing them a "proper" chart was meaningless to them.

So producers and arrangers created a system, based on simplified music theory and the Major scale, to help them understand how to learn and play songs quickly. After learning this "system", they were now able to learn any

song within a few minutes, and lay down a recording within 20 minutes or so. As this method took hold, music directors would sit down before the session began and call out the progressions - using this numbers system - and

the arrangement (how the song is put together).

That is a simplified explanation of how it came about. The deeper point here, and what you are going to learn, is that the Numbers system can help you immensely when it comes to learning a song - even one you have never

heard before - and have you able to play it in a few minutes (versus hours). An added benefit is that it also helps in transposing the song to another key for the singer (to help them sound great). Now, that's a scary

topic, transposition. But it really isn't as complicated a process as you think - particularly when you use the Numbers system.

First, everything is based on the intervals of the Major scale. So, if we are in the key of G, here is how you would lay it out:

While in the Country circles they use standard 1, 2, 3, etc. numbering, many do not, but you should still make a mental note about standard numbers. Therefore, in order to be consistent with the broader approach in most

music circles, we will be using Roman numerals instead of regular numbers.

For those who do not know Roman numerals, they are really quite easy, and we don't need to count beyond seven.

Capital numerals are used for Major family chords: I (1/G), II (2/A), III (3), IV (4/C), V (5/D), VI (6E), VII

(7/F#)

Lower case are used for minor family chords: i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi, vii

Adding extensions and/or numbers to it will call out the specific chord type. Let's stay in the key of G. So a I alone is G major; Imaj7 is a Gmaj7;

I7b9 is a G7b9; I+ is augmented

(#5), so written Gaug or G+ even G#5.

Likewise for minor based chords - still in the key of G; C is the 4th interval of the scale, but here it is minor: iv alone simply means Cmi; iv7 means Cmi7;

iv7b5 is half diminished, so, Cmi7b5.

The numbers dictate the interval position of the chords.

Now, how do you use this stuff?

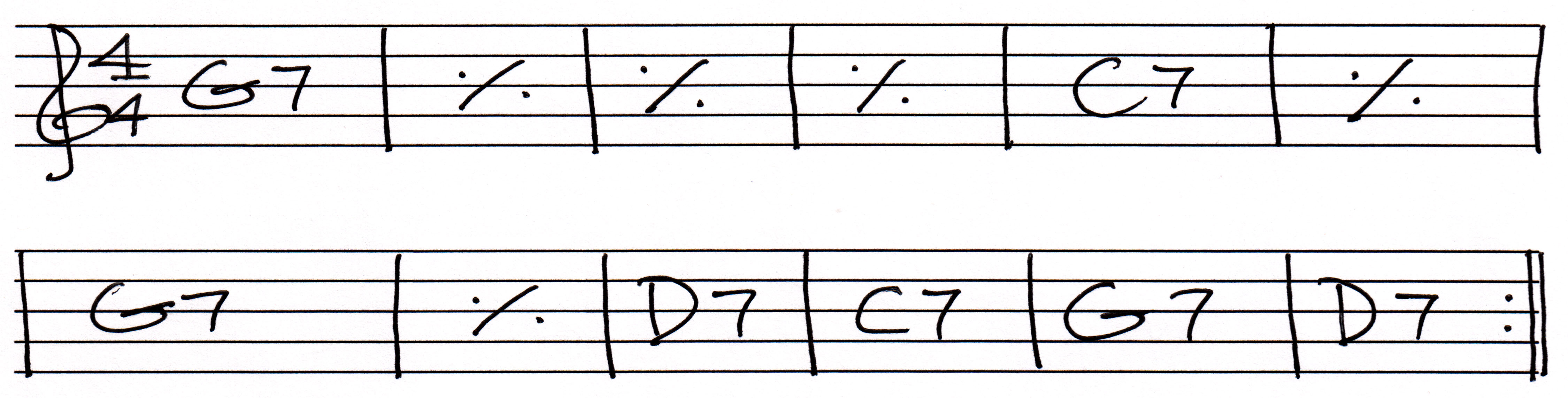

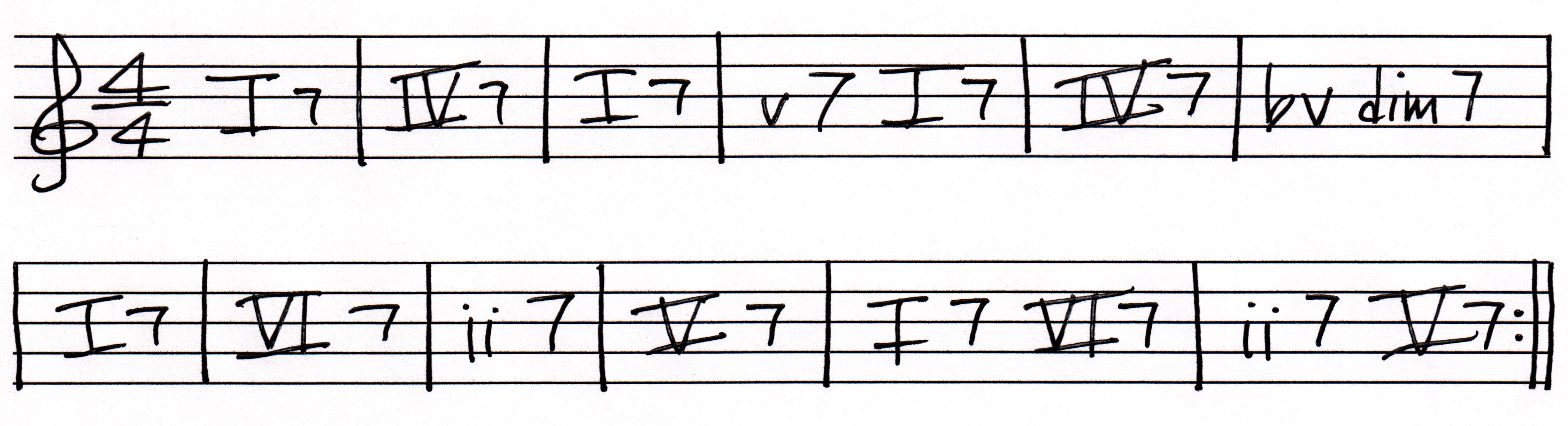

Starting easy, let's take a simple Blues tune. You've heard it called the "one - four - five", right? Well, now you will understand why. So here it is written out in the key of G.

G - 1

A - 2

B - 3

C - 4

D - 5

E - 6

F# - 7

G - 1

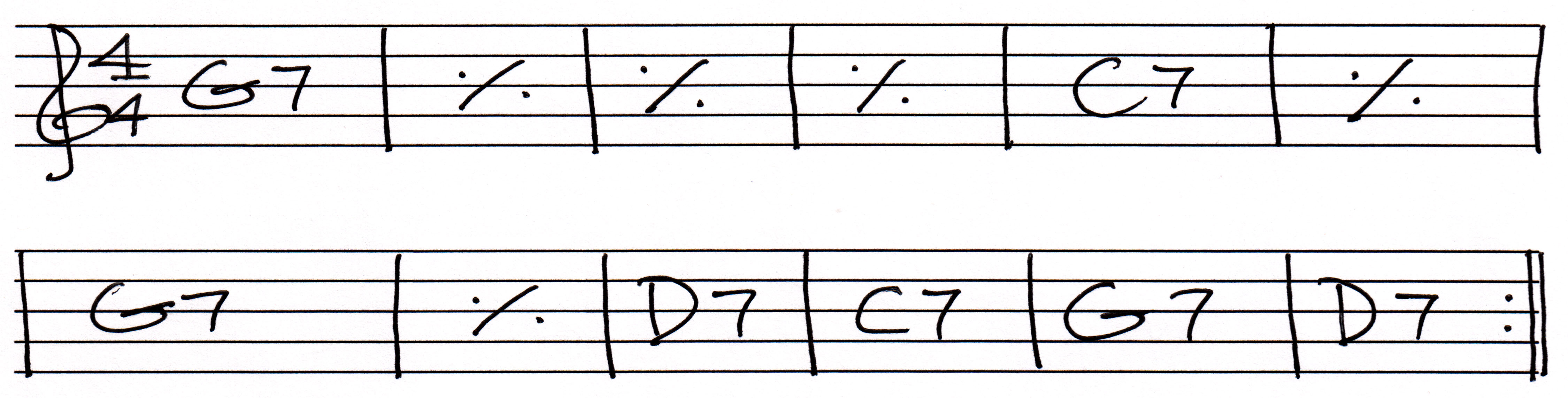

And here it is converted to numbers:

Pretty easy, right? Okay, now from the key of G, play it in the key of Bb. Take your time. When you have done that, move it into the key of C. Then, Make it a fifth string root in E, and play it with all Barre chords. Do the same with the key of D. All you're doing is moving a pattern around now. That's a whole lot easier than trying to transpose something when you aren't very good at it. This makes transposing easier on simpler stuff.

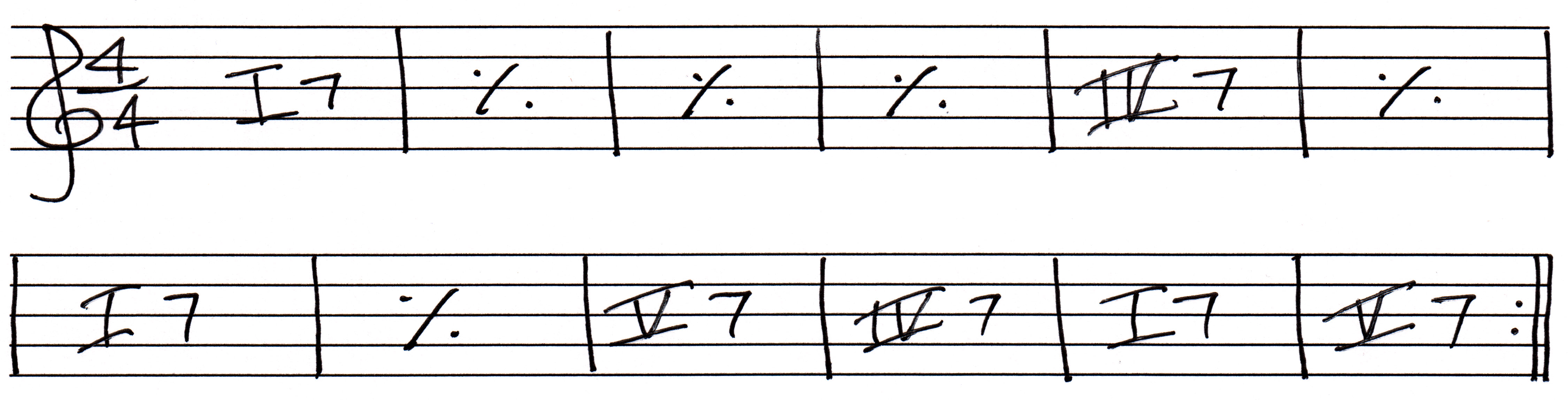

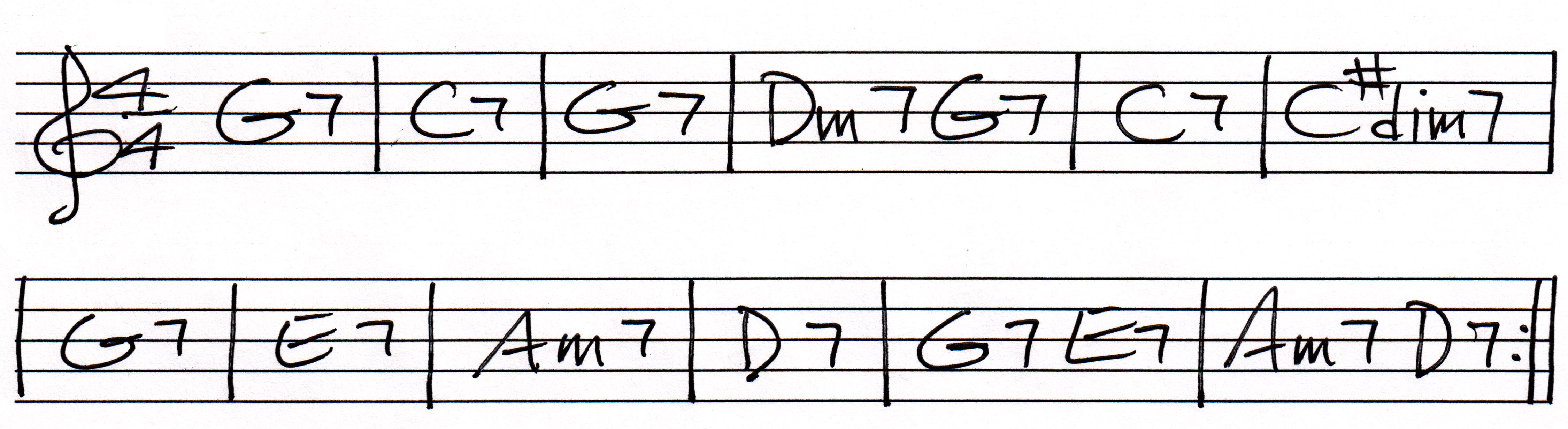

Let's take a more involved Blues progression and do the same thing. Here is the arrangement as you might normally see it, still the key of G:

Now with numbers substituted in their place.

Take notice of measure 6, the dim7 chord. In the first chart, it is C#dim7, which raises the C root by a half step. But in the number chart, we lower the pitch from above, from the V chord position, to make it a bV. The #IV (or #iv) chord designation is not used. This is one of those rules of music notation, that some ways of writing things are preferred, for simplicity and clarity.

Once you have the pattern down, and think you can change keys, move it into Bb, then C.

You can do this with any tune. You start with the key (in this case G) and that becomes the I chord (or i if it is minor based). Just remember the simple rule of major and minor indicators for your chords. Capital Roman numerals is Major based, and lower case Roman numerals is minor based. Then you add the appropriate extension, just as you would normally do if you were writing a regular chart in a specific key.

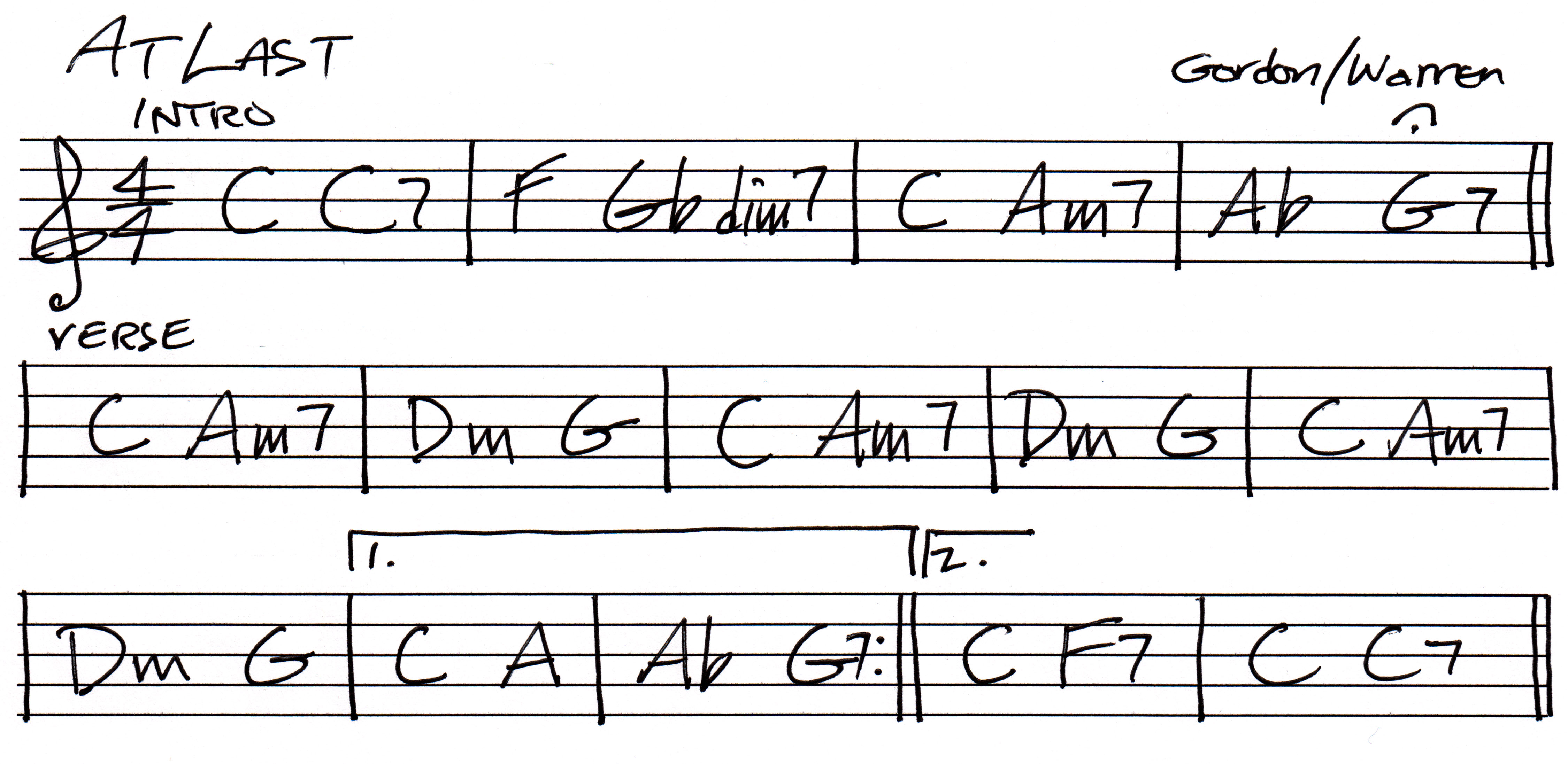

Let's take a classic tune, At Last, in the key of C. Here's a standard chart:

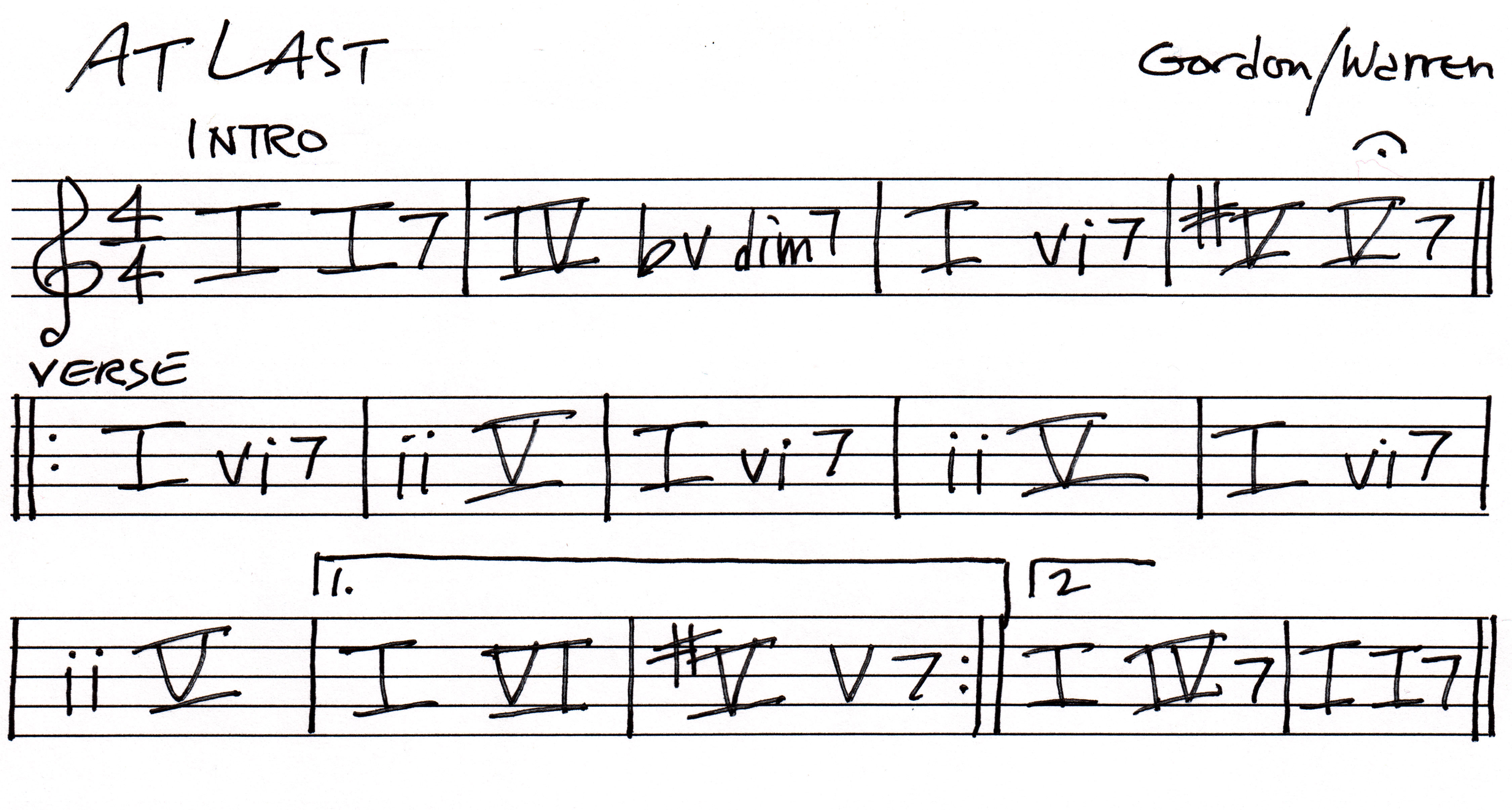

Now let's swap out the chords for their number equivalents, which looks like this:

Just a reminder: When a "b" appears before the numeral, you flatten or lower the position one-half step;

when a "#" appears before the numeral, you sharpen or raise the position one-half step.

And, remember, just as you lower the V chord flat (not raise the IV chord sharp), you also raise

the V chord sharp, not lower the VI

chord flat. The same clarity rule applies.

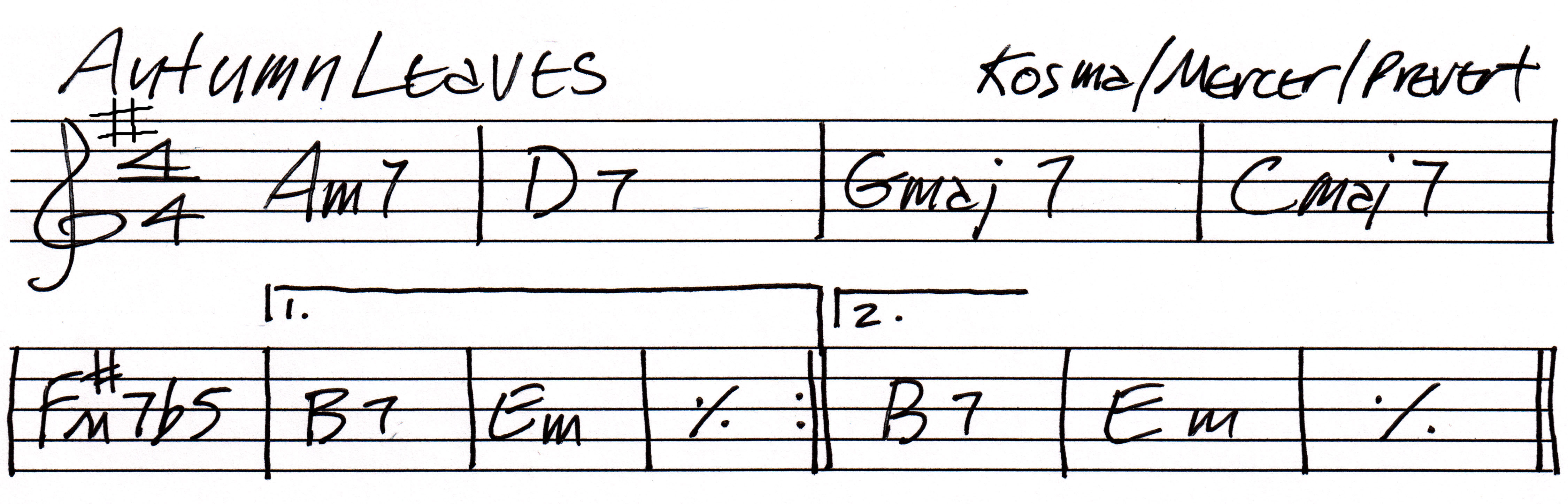

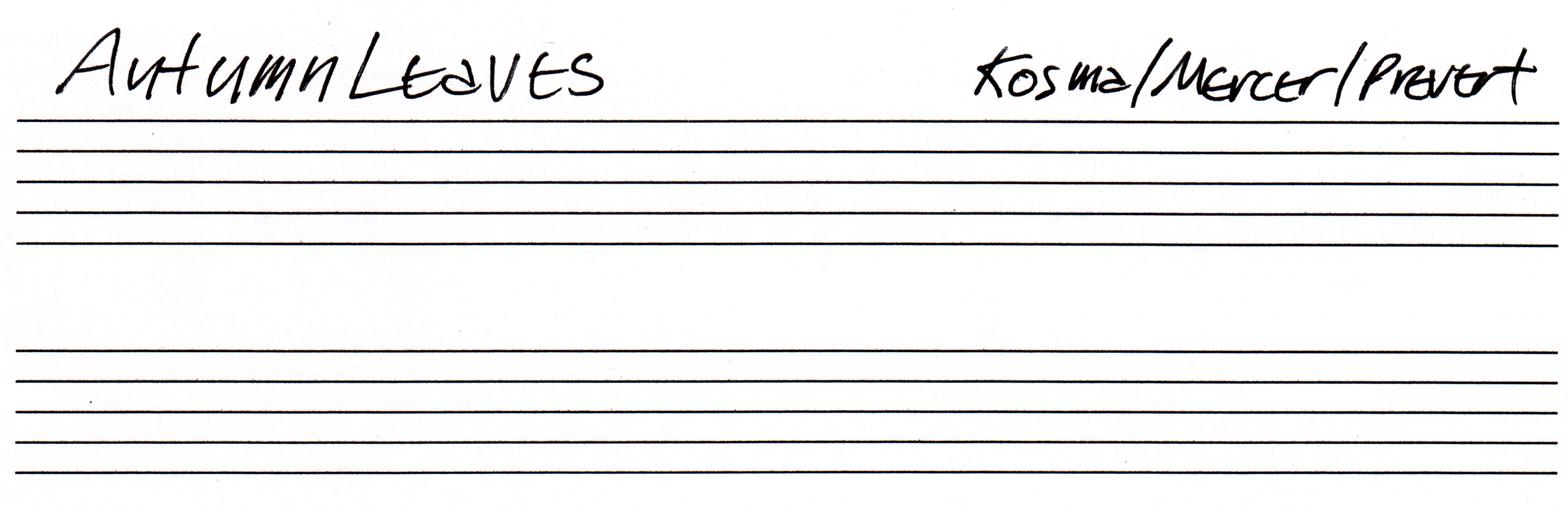

Okay, you're getting the hang of this, so here's Autumn Leaves, the A section:

Now, you fill in the numbers. You can right click the chart below and copy or save it ("save as" or "save target as") as a .jpg and print it out.

What makes this approach to making charts so

cool is the fact that you can move this into any key. All you have to do is

establish an understanding of the pattern you are playing - the relationship

of the chords to one another – and the key center.

As mentioned before, if we are in the key of C Major, how far is an Am7 from

the C root/key tone, fret-wise? And then, where is the next chord as it

relates to the C? All chords in a

progression will have their designation based on their relationship to the root/key tone chord.

Then, by establishing the progression’s

pattern, you can quickly move the whole arrangement to a different key - where

your singer sounds best (assuming C is not good for them on this song).

You need to try this! Seriously.

Take charts of songs you know and create new

charts using the number system. Practice this until it becomes easy and you can

change a chart over in a matter of a few minutes. This works best on pop,

country and easy rock n' roll tunes, and also works with Top 40 style stuff and

Jazz standards that are set pieces.

More progressive songs are not very conducive

to this system - they're too convoluted and involved for this to work well. In

other words, the more complex songs by Ozzy, Dio, Deep Purple, Zeppelin and

others like these generally aren't going to be well suited to this system.

It's not rocket science, but it may hurt your

brain a little bit until it clicks into place. I've written charts out employing

this approach - only numbers - and used them in real situations. When people

understand how they work, the key just becomes a place holder where

everything sits. And when you work with more than one singer, you don't have to

create a new chart in another key (though I may make notes on the side about

any relevant alterations in the arrangement). This covers it all very well.

We could interject stuff about shifting key

centers in the middle of a song, but that would make the process more

difficult. Unless there is a defined change in key, like a modulation from the

key of A to the key of B, for example, there isn't any real need

to deal with that. The object here is to highlight the pattern of a song, and

that using this system allows you to write charts in numbers, not a specific

key, so that you can play it in any key more quickly and easily -

even do so on the fly. And that is powerful stuff.

We're all "students", even after many years of playing. There's always more to learn! Now shut off your computer and go play with some ideas.

See you next time.