In this first installment, I want to cover the idea of chord names. You know, the chord 'call out' above the written music that looks something like this:

How do you decipher all that? It's really quite easy, really, and most players can readily identify these and know what they mean, and hopefully also play them as the music requires. If you can't, we'll get to how to build chords soon, but not in this column.

Let's start with something simple, though. That way, it will all make more sense.

When you encounter a chord call out, it is giving you information you need, information it assumes you understand, or at least can either figure out or ask someone to show you. Therefore, beginning with an easy one, let's take the C Major chord. It is usually just written in a call out as “C”. So, the rule here is that when you encounter a chord without any other ‘stuff’ attached to it, you play the Major version only. So, whether it is a G or an E or an A - or whatever chord being called out, all are rendered as the simple Major versions of the chord with no added 7ths, 9ths or flatted this or sharp that.

Major chords are composed of only three tone intervals: the I (C), the III (E) and the V (G). No other notes are included! Note, too, that all chords, whether Major, minor, diminished, dominant, augmented or suspended, are built upon the intervals of the Major Scale, you know, the do, re, me... scale. Anyone who tries to tell you otherwise doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

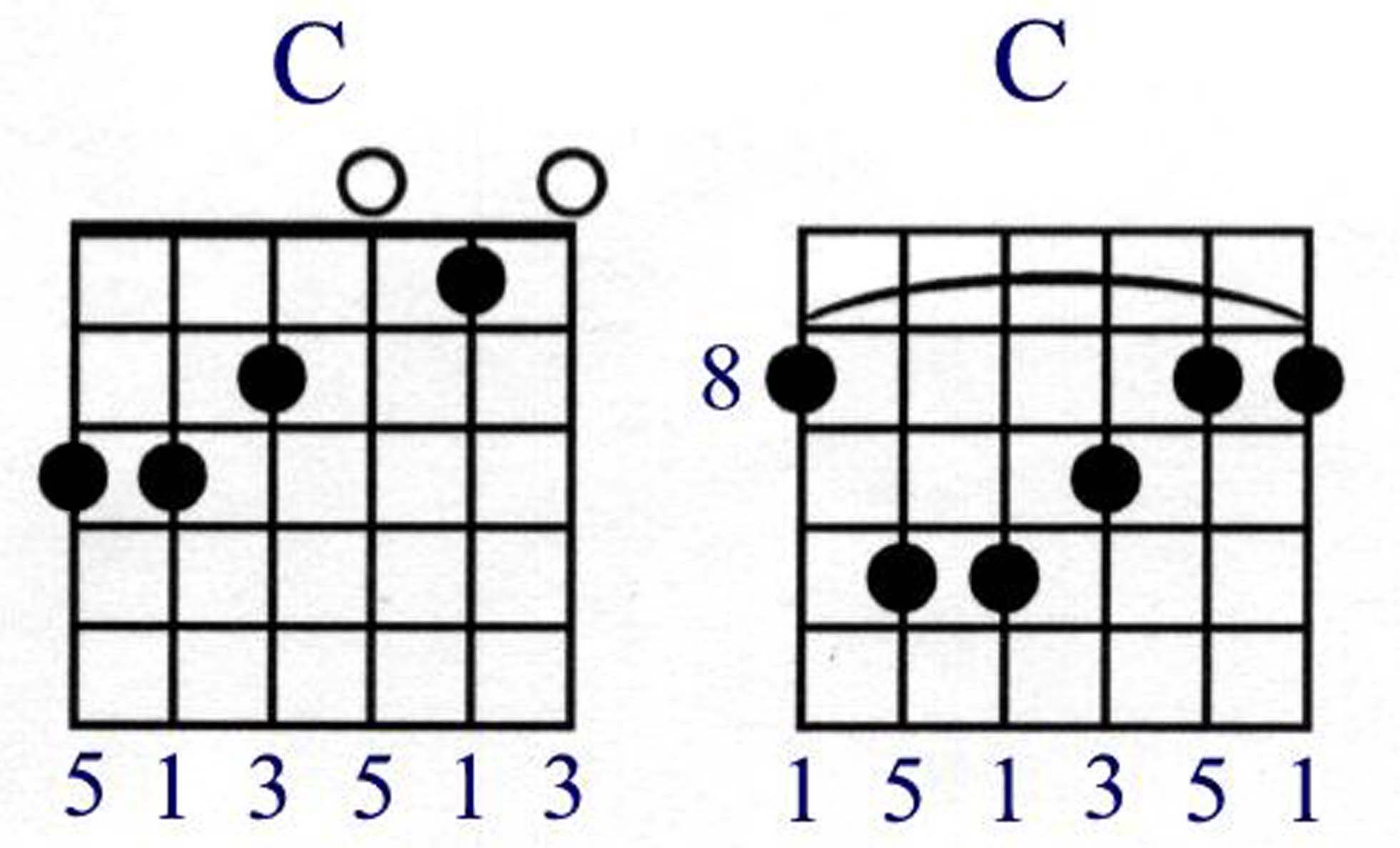

For the sake of simplicity, let’s just use standard numbers to reference the intervals. In the following diagram, you will see two versions of the C chord. Each shows the intervals called out below the diagram. We already

know the ‘spelling’ of the chord: C, E, G.

Okay, you say, so what about Dominant chords? How do I know it’s a Dominant chord?

While we talk about Dominant chords in using the term “Dominant”, we generally will prefer to use a ‘short hand’ reference to this chord family. We would call them 6th, 7th, 9th, 11th or 13th chords, dropping the term ‘Dominant’ from the discussion.

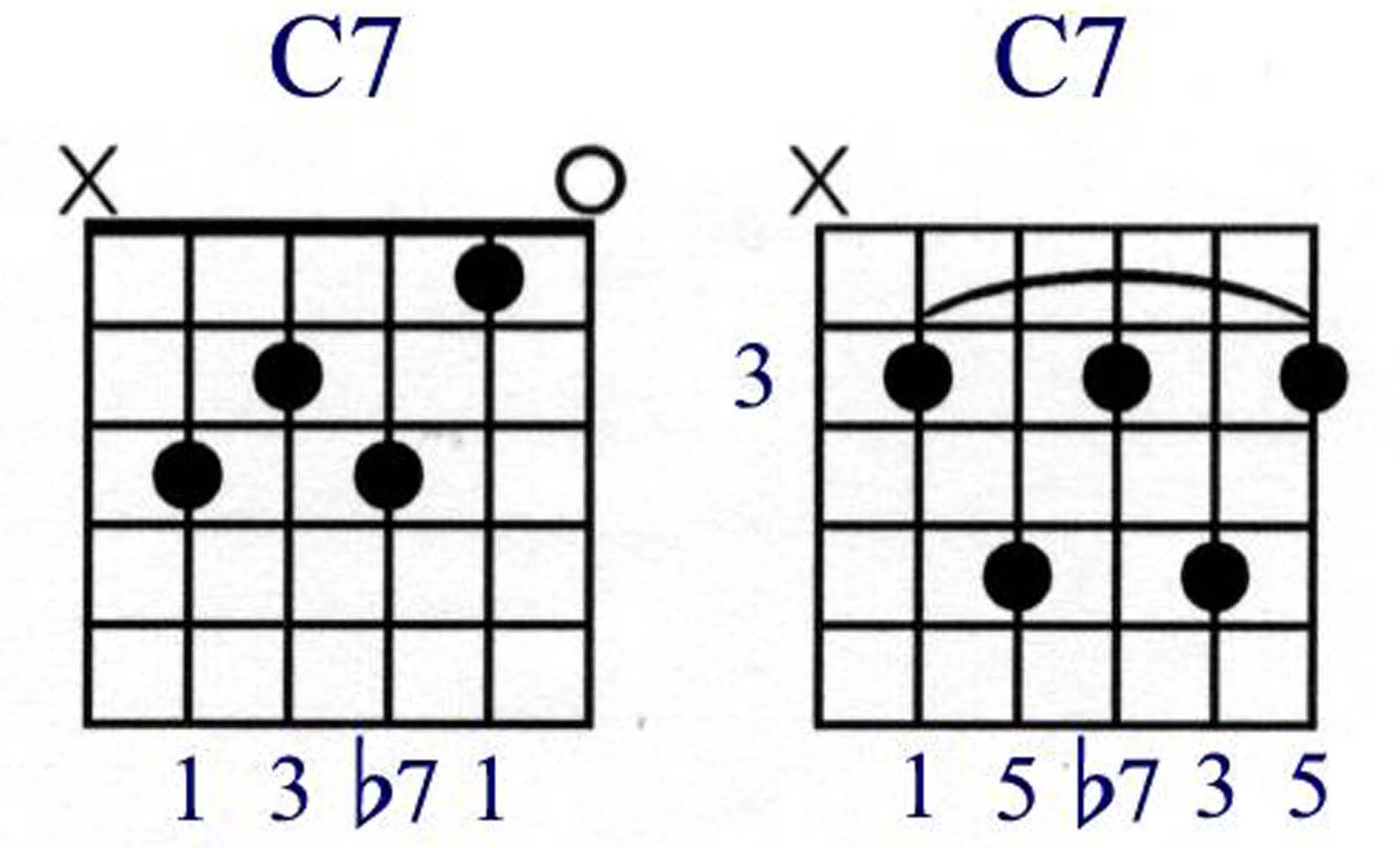

A typical Dominant chord contains four basic elements: the 1, the 3, the 5 and the flatted 7 (b7) - except in the case of the Dominant 6 chord

(1, 3, 5, 6). You would build upon this four note foundation for 7th, 9th, 11th and 13th chords. So, a Cdom7 (written as simply “C7”), your tone intervals will be: 1 (C), 3 (E), 5 (G), b7

(A#). Here are two versions of a Dominant 7 chord:

It becomes an assumed understanding (by someone telling you what I just said) that you know what is being referred to when we talk about, say, playing a 7th chord in the IV of a progression (as with typical Blues progressions, which are ‘short hand’ referenced as a I, IV, V). If this is getting a bit deep, don’t worry, we’ll cover it in another column on Intervals.

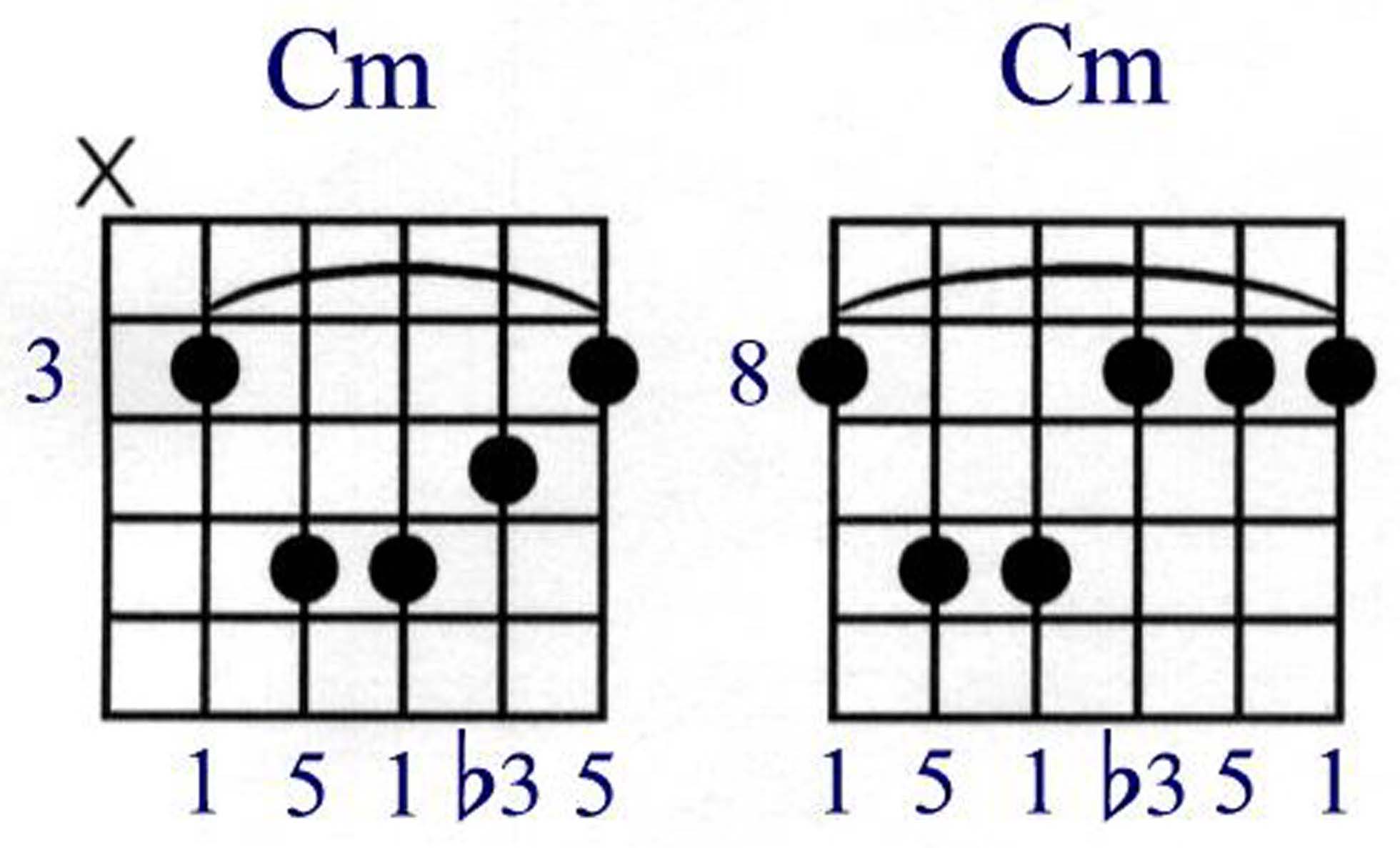

And with a standard minor chord in C, it will be written like this: Cm or Cmi.

Like the C Major, the C minor is a straight and simple minor chord, with no added anything to it. A minor chord is composed of three basic elements: 1, b3, 5.

Where in C Major the 3 tone is a perfect 3rd interval (E), in a minor version of C, C minor (Cm or Cmi), the E tone is now flatted; it is moved down, lowered by one half step (one fret) to

Eb. So, in the following two examples of the C minor chord you will see just how it stacks up.

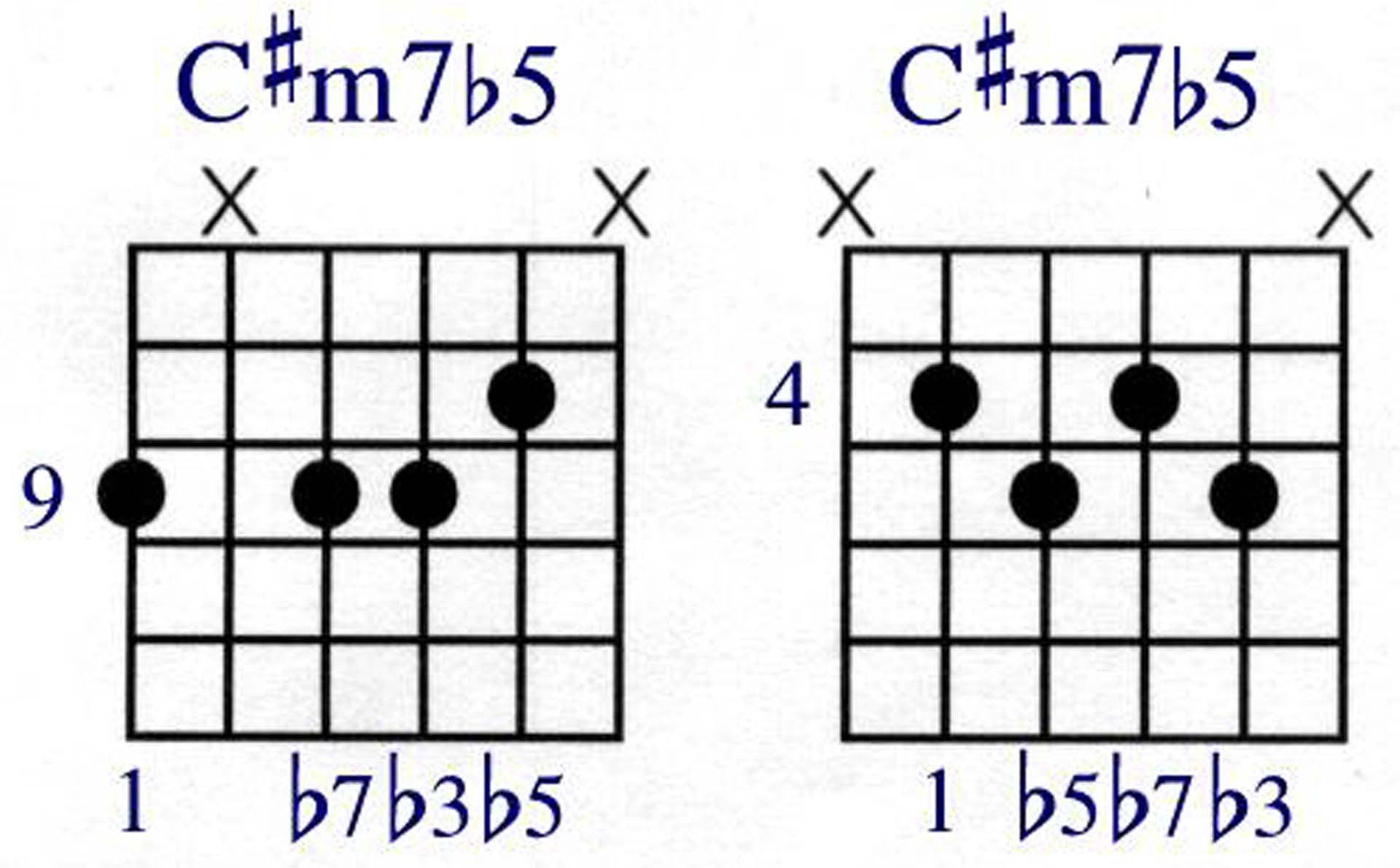

Okay, but what about some of those really ‘fancy’ chords with lots of stuff added to them, like that C#-7b5 in the graphic above (which can also be written C#m7b5)? What’s that all about?

This chord is one that conveys a whole lot of information in a very compact fashion. We see that the chord is a C# positioned chord. We see that the “ - ” symbol is another ‘short hand’ way to indicate that it is a minor version of the C# chord; the “7” right after shows that it is specifically a minor 7 version of the C# chord, so the 7 tone is lowered, or flatted one half step (one fret). The b5 means this minor 7 chord has an altered 5 tone, being made flat or lowered (diminished ) by one half step (one fret).

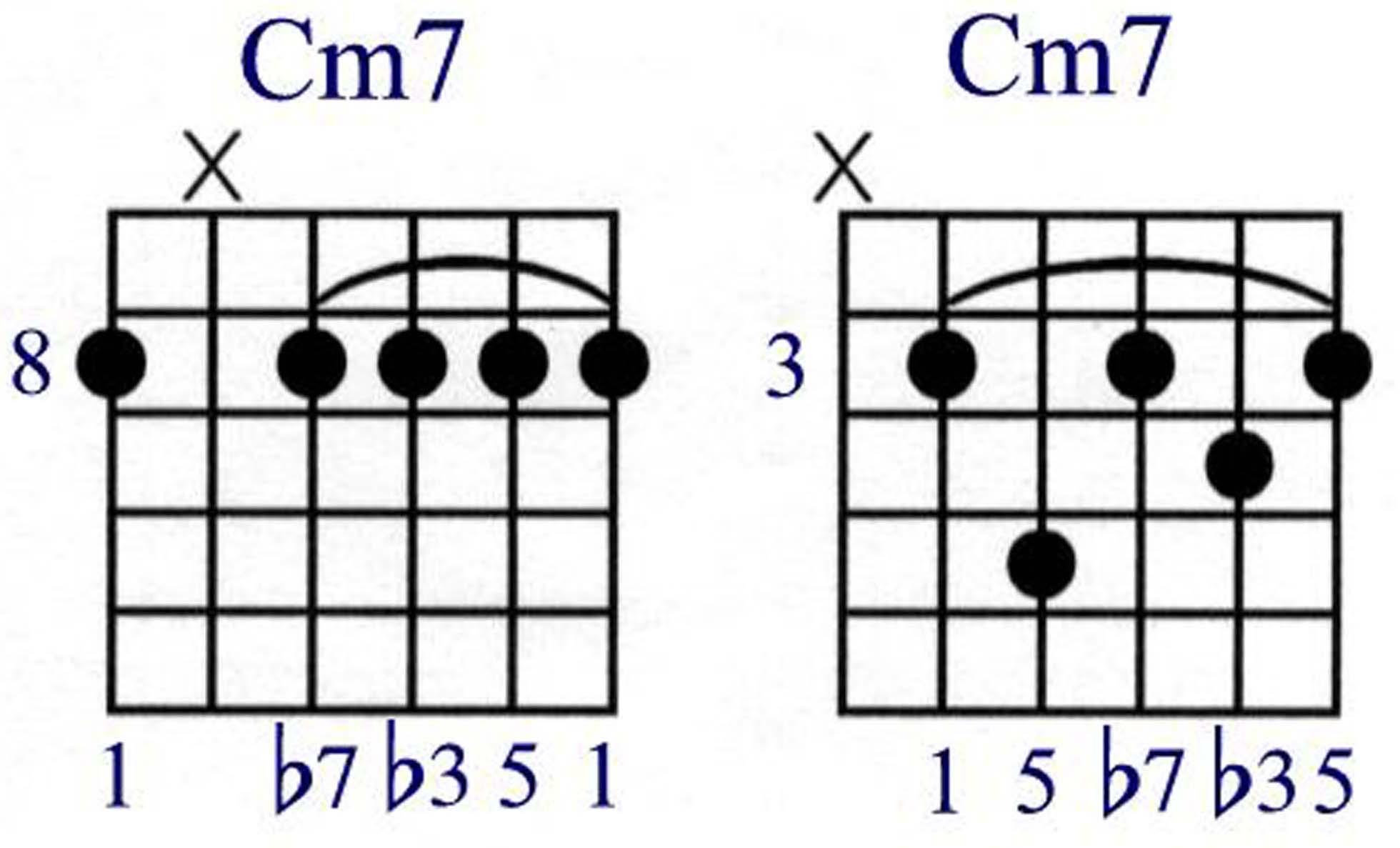

Basically, the minor 7 chord is composed of the following intervals: 1, b3, 5, b7.

The 3 and the 7 are one half step flat - lowered - from their perfect state. So in the example of the C#m7b5,

it would contain these notes: 1 (C#), b3 (E), b5

(G), b7 (B). Remember, the 3 tone determines the Major or minor status of a given chord. In the diagram

below are shown two versions of a typical minor 7 chord in the C position:

Now that brings us to the complete chord: C#m7b5. As mentioned above, this chord has

an altered 5 tone; it is flatted, or lowered, one half step (one fret). So it would look like this:

This is a subject that can get real deep real fast, and I could go on and on with numerous examples. But rather than tackle everything, we will bring the whole subject to light over the course of multiple articles - even it’s own section - as we move forward. To be sure, chord construction is a very fascinating subject that far too many guitar and bass players tend to neglect as they move forward in their progress.

I can’t tell you how many players I know who can play just about anything, but couldn’t tell you what chords (or scales) they are playing. They just know it sounds really good when they put them together in certain ways. And it does. But this kind of ignorance is really difficult to deal with when you’re trying to learn something quickly and effectively - especially in a live jam. I’m not saying these people are stupid. Ignorance simply means ‘lacking knowledge’. And these people have knowledge, in that they know how to play anything, but they lack the ability to explain what they do in terms that will convey what they’re doing easily and quickly. If they knew what their chords/scales were, they could rattle them off or write them down for another player, and both would be up and playing quickly and with minimal problems in interpreting the music in question.

I hope this has helped to clear up some of the confusion about chord call outs and how you understand the ‘language’ used in writing them out.

If you have some suggestions for columns, feel free to let me know: Suggestions, and please write “suggestions” in the subject line.

Until next time, keep expanding your knowledge. And for you beginners, remember this: All guitar players you admire were exactly where you are today. If they can grow past this, so can you!

Now shut of the computer and go put in some time on that guitar!